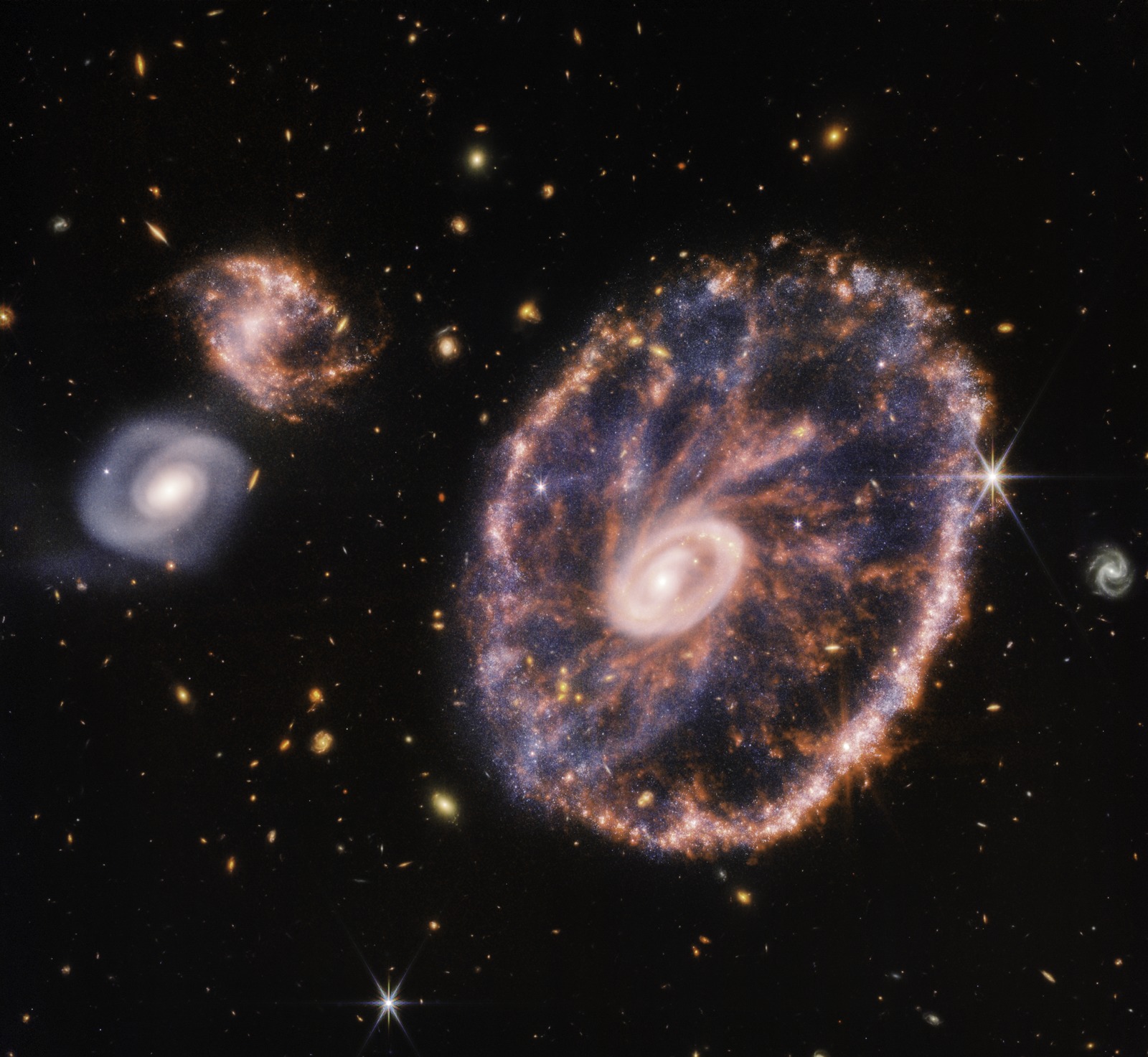

The James Webb Space Telescope has taken an intriguing image of a cosmic accident victim — a large galaxy that was hit directly in its center by a smaller neighbor. Called the Cartwheel Galaxy because of its appearance, this distant grouping of billions of stars was hit by a cosmic bullet — small spiral galaxy that pushed right through it hundreds of millions of years ago. (The “bullet” galaxy is not visible in this image, but we see in other pictures.) The two rings we see so clearly in our image are the result of that collision.

The Cartwheel is about 500 million light-years away, and has a diameter of about 150,000 light-years (where a light-year is about 6 trillion miles, the distance light travels in a year.) Like many such flat galaxies, it contains billions of stars and lots of cosmic “raw material” — gas and dust, from which new stars and planets can form. So when a much smaller galaxy collides with it, the bigger one survives the accident, but has ring-like “scars” to prove it. Astronomers think that the spokes we see between the wheels are spiral arms which are trying to re-form after the accident.

Remember that the Webb doesn’t take pictures in visible light, but rather in infrared (heat rays.) So the colors are selected by the science team to bring out important information in the images. On this picture, reddish colors show us cooler dust, while bluish colors show us warmer regions where lots of stars are forming or have formed.

One of the most significant effects of such a collision is to generate “shock waves” that cause generations of new stars to form, something that is happening especially effectively in the outer ring. We think many of the “mature” galaxies we see in the universe today had their structure sculpted by a whole series of such collisions. In our own majestic Milky Way Galaxy, we still find unusual “streams” of stars left over from smaller galaxies that we absorbed over the eons.

By the way, if you are fan of cosmic distances, you might be surprised that galaxies could be close enough to collide, when stars within a galaxy rarely do. That’s because, compared to their sizes, stars are far apart, but galaxies (especially in groups) can get much closer together. And recent surveys show us that galaxies often congregate in groups, and thus can powerfully affect each other’s development. Social interactions are as important for galaxies as they are for humans, it seems.

(If you’d like to see the Hubble Space Telescope’s visible light image of the Cartwheel, you can find it here: https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/goddard/2018/hubble-s-cartwheel In this image, you mainly see the hot stars of the galaxy, while the Webb image shows you all the cooler dust and dust-shrouded stars that the Hubble can’t see.)