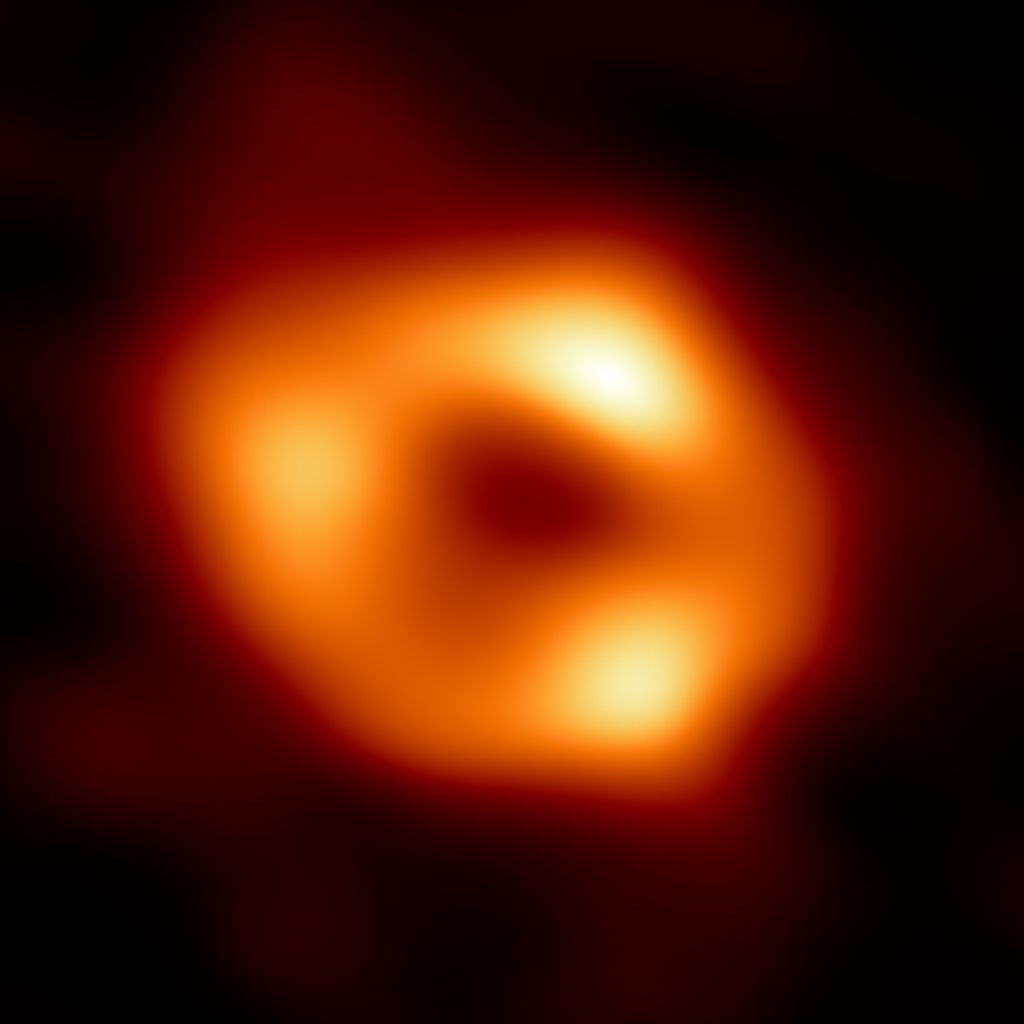

An international team of astronomers, working in the collaboration known as the Event Horizon Telescope, has announced the first image of the monster black hole at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. The data were actually obtained in 2017 using 8 telescopes spanning the world, but it took until 2022 (and several supercomputers) to produce an image that shows the shadow of the black hole on the glowing disk of material around it.

Our Galaxy’s central black hole is known to contain enough material to make 4 million Suns! It is 27,000 light-years from us, which means that we see the black hole about the same size as a donut on the Moon would be when seen from Earth. To make things more difficult, the gas near the opening of the black hole is moving around it in only minutes — it’s hard to produce an image that isn’t completely blurred when things are moving that fast.

The image that the team released was not taken with visible light, but with radio waves. So the picture is artificially colored to help our eyes distinguish the glowing gas (orange) from the dark shadow of the “event horizon” (outer limit) of the black hole itself. But in the dark region on the photo you are looking at a “one-way door out of our universe,” as one of the scientists said. A black hole is a place where stars and other materials have collapsed so dramatically, that gravity prevents anything and everything from escaping.

Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel received the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics for demonstrating the existence of this black hole — by monitoring the fast motion of nearby stars going around it. But no one has seen the black hole itself until now. Eventually, astronomer hope to produce a movie of the inner region, but for now it’s great to have the still image.

In 2019, the same team released an image of a much larger black hole in the galaxy whose catalog number is M87. There, the black hole was bigger and the gas around it was moving more gradually, so the image was easier to tease out of the data. In both cases, the observations had to be compared to many different theoretical models of black holes surrounded by gas to get the best fit. Although the images look blurry at first view, we are actually seeing better “resolution” — more detail — than the Hubble Space Telescope can show at these distances. It’s wonderful to have images of the “open jaws” of giant black holes available.